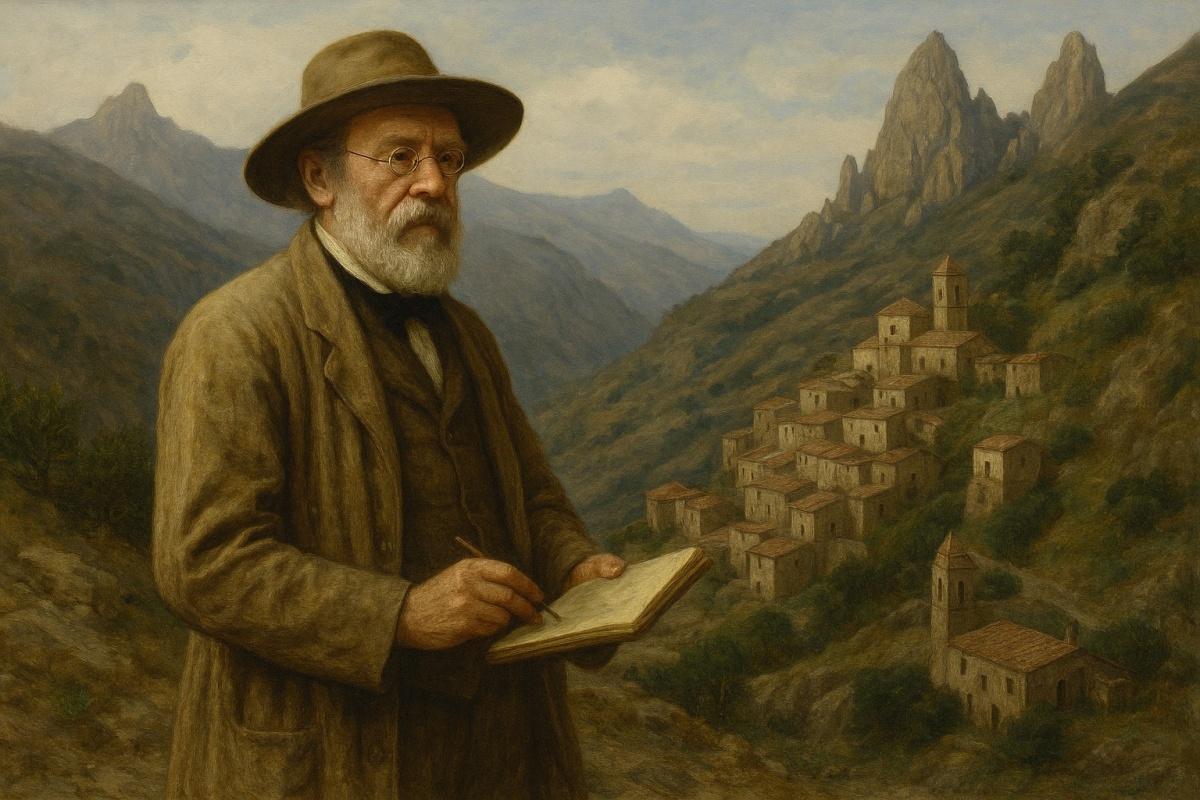

In 1847, Edward Lear — artist, writer, naturalist, and British traveler — undertook an extraordinary journey through Southern Italy, reaching the most remote and fascinating corners of Calabria. His itinerary included not only major cities but also the most isolated and captivating villages of the Grecanic Area, in the heart of Aspromonte, leaving us one of the most poetic and detailed accounts of that region in the 19th century.

Journey through Calabria (1847): an adventure from another time

Lear traveled on muleback or on foot along steep paths and dry riverbeds, often accompanied only by a local guide. He visited Bova, Condofuri, Roghudi Vecchio, Gallicianò, Pentedattilo, and other villages that were then almost inaccessible, capturing in his travel notebooks and delicate watercolors all the charm of places suspended between myth and reality.

In his Journals of a Landscape Painter in Southern Calabria, Lear enthusiastically described his experiences, mixing landscape depictions with cultural and linguistic observations. For him, Calabria was not merely a place to “explore,” but to understand and narrate with respect and wonder.

Language and Grecanic culture: an ancient and living heritage

Lear was fascinated by the presence of ancient Greek, still spoken in many villages of the Grecanic area, in a dialect now known as “Calabrian Greek.” He was intrigued by this unique phenomenon: a population in Southern Italy that, in the 1800s, still preserved customs, sounds, and words of Byzantine and Magna Graecia origin.

He described with interest the religious rituals, folk songs, traditional clothing, and simple yet symbolically rich architecture. Many villages reminded him of epic Homeric settings or Byzantine icons, and in his writings he often compared them to ancient Greece and the Holy Land.

Works and watercolors: the South as visual poetry

During his stay, Lear created dozens of sketches, drawings, and watercolor paintings now preserved in major institutions such as the British Museum, Tate Britain, and the National Gallery of Ireland. His visual works didn’t merely reproduce landscapes: they sought to capture the soul of the place, with a chromatic sensitivity that foreshadowed impressionism.

Alongside the watercolors, Lear compiled a series of journals and letters, now a valuable source for historians, linguists, and anthropologists interested in pre-unification Calabria. These documents are also a testament to how Southern Italy was perceived by European travelers of the time.

Bova: a declared love

Among the visited places, Lear reserved particularly intense words for Bova, the cultural capital of the Grecanic area. He called it "one of the most picturesque mountain sites I have ever seen". He was struck by its scenic position, architecture, views of Mount Etna and the Ionian Sea, and especially by the dignity and pride of the people, living in harmony with nature and with a centuries-old cultural heritage.

He spent a long time in the village, drawing alleys, churches, and scenes of daily life. His notes also described the social conditions and economic hardships, always with respect and without condescension.

An anthropological and human gaze

What distinguishes Edward Lear from many other British travelers of his time is his deep empathy towards the local populations. Where others saw backwardness, he saw authenticity and culture. While many recorded only landscapes, he focused on traditions, legends, songs, and gestures.

At a time when Calabria was often described as “wild” or “barbaric” by the Northern European press, Lear offered a fairer, more intimate, and participatory narrative. He had the eye of an artist and the heart of a respectful, curious traveler.

A legacy that still speaks

Today, Edward Lear’s legacy lives on in his drawings and writings, but also in the trails that cross Aspromonte and in the villages where Greek is still spoken and ancient rites are preserved. His works can be seen as a precious time capsule: a narrative of the Grecanic Area before the 20th-century changes forever altered its face.

Visiting these villages today — from Roghudi Vecchio, abandoned yet fascinating, to Gallicianò, a symbol of the Hellenophone cultural revival — means following Lear’s footsteps and being enchanted by a Calabria still little-known, deep and full of identity, which once spoke to the heart of a 19th-century English artist… and still does today.